Corn Prices, Farm Returns, and Appreciation Rates

While doing some work for a client recently, we pulled together several charts that have very similar patterns: Net Cash Farm Income, the rolling nearby corn futures price, and the NCREIF US Rowcrop Farmland Appreciation rate. What they tell us is that low corn prices have a surprising effect, well outside of the corn belt.

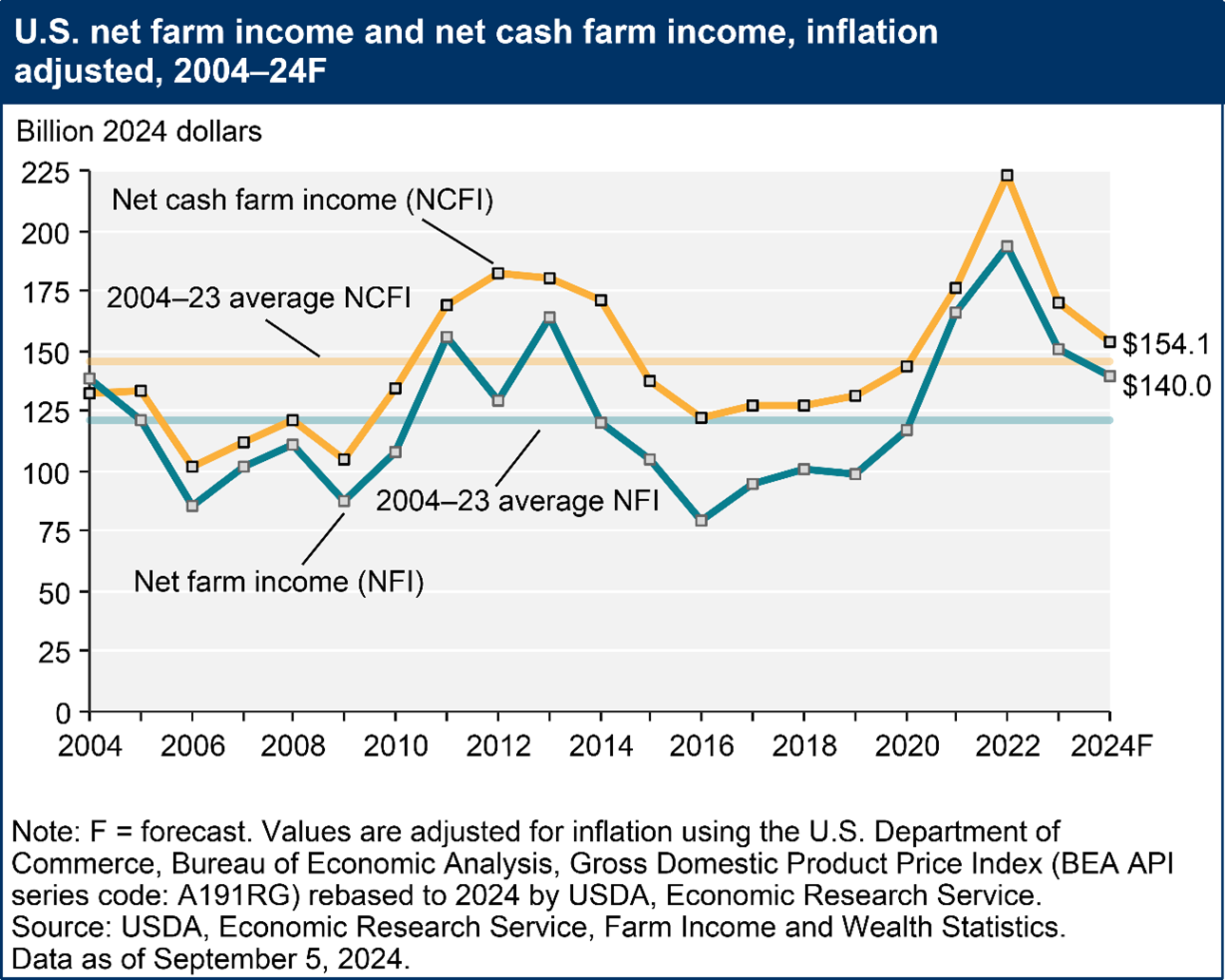

First, let’s look at the inflation adjusted US net farm income projections from USDA/ERS, in particular from 2010 through to September 2024. Note that after four years of low figures, there was a significant bump in farm income starting in 2010, peaking in 2012, and then bottoming out again in 2016. This was followed by three more years of low income. It then begins to increase with COVID in 2020, peaks in 2022, and is now on the way down again.

The second chart overlays the daily rolling nearby corn futures price in gold and on the left vertical axis with the NCREIF rolling quarterly average appreciation rate for rowcrop land in the US over the same time period depicted as the red line. Starting to see a pattern? Although the rowcrop land appreciation rate has a 1 – 3 quarter lag behind corn futures prices, they both move very much in line with the USDA projected net farm income above. This is further overlaid with the 2024 Iowa State University corn breakeven cost per bushel, including cash rent of $285 per acre, assuming a 185 bushel per acre yield. Subtracting the cash rent would bring the breakeven price down to about $3.60 per bushel. The significance of prices vs. breakeven costs is that it implies additional returns to the land will be limited until commodity prices increase.

So, not surprisingly, it appears farm income and rowcrop farmland appreciation rates are well correlated with corn prices. What may be more surprising is that the crop that gives the “corn belt” its name also influences row crop prices in nearly every other major production region of the US. The table below shows both NCREIF quarterly appreciation rate correlations between regions and between all US rowcrop (Annual) cropland with those regions. While the Corn Belt shows the highest correlation of appreciation rates with Annual cropland at 0.829, the Delta region is close behind at 0.824 and Pacific West Annual cropland (California) at 0.738[1].

So what are we saying here? First, if US rowcrop farmland returns are influenced by corn prices, and the US regions are correlated with the US rowcrop returns, it then follows that regional returns are also influenced by corn (and likely other commodity) prices. Secondly, we are likely to see reduced appreciation rates for as long as corn (and other commodity) prices remain relatively low. And finally, if these relationships hold, we are likely to see these reduced return rates for the next few years until commodity prices rebound.

For Contrarian investors, just as in a down stock market, this could represent a buying opportunity. A conservative approach would be to stick to highly productive ground in prime growing regions such as the Mississippi Delta and the Corn Belt. A more aggressive strategy would be to target regions in the Intermountain West, Delta, and Southeast with senior water rights that will benefit as specialty crop acreage in California is forced by water curtailments to seek new production in other regions. And for the truly contrarian, look for properties in California that have both the senior water rights and the supply to survive over the long run.

[1] There are some statistical caveats to note here; The NCREIF Annual Cropland appreciation rates are the weighted average of appreciation returns in across all regions, so there is some co-linearity going on here between “Annual Cropland” and individual regions. We are also operating under the logic and assumption that if US rowcrop farmland returns are influenced by corn prices and the US regions are correlated with the US rowcrop returns figures, it follows that regional returns are also influenced by corn prices.