Peanuts #3: Factors of Peanut Supply

by Sidnee Hill & Matt Harrod

We began our discussion on peanuts on how the humble legume holds promising strategic opportunities for farmers and investors alike. The data we explored in our second article shows that demand growth, both domestically and internationally, continues to hold strong. All that remains, then, is to understand how US peanut producers fare in supplying that demand and what risks they must overcome to do so.

In the 2023 crop year, US peanut farmers produced 5,890 million pounds of peanuts on 1,574,000 acres. As we can see from the chart below, total peanut farmer stock supply can change significantly from year to year. Since the farm level supply of a commodity deeply affects not only the price received at the farm gate, but also throughout the supply chain, it is important to dissect the influences and drivers of that supply.

There are at least 6 things that can increase, or decrease, our supply of a commodity: 1. The amount of acres able to produce that commodity, 2. Expected returns from competing activities, 3. Input costs of production, 4. Changes in production technology, 5. Natural events and, 6. The farmer’s expectations for the upcoming market conditions[1]. Let’s look at each one of these factors in turn to better understand the production of peanuts.

Acre Availability

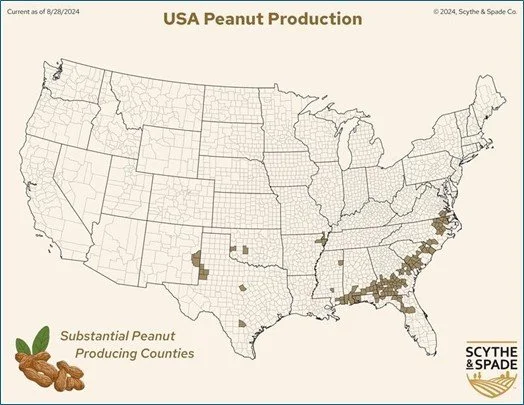

Peanuts require very specific conditions in weather and soil in order to be viably grown for commercial use. Revisiting our map from the first article, we quickly see that US peanut farming is primarily focused along the southeastern coast.

The composition of the soil in the region, being sandy, well-drained, and highly fertile, is the perfect combination for peanut production. This region also boasts the long growing seasons and warm temperatures needed for high peanut yields. Very few other regions in the United States meet all of these necessary conditions and so, by a product of environment alone, supply is limited by the finite acres that can even grow the crop.

Expected Returns from Competing Activities

This high-quality peanut ground is also prime farmland for many other crops. Our second driver of supply reasons that a farmer will consider all possible uses for that land and will choose the one that maximizes potential return relative to risk. Logically, this makes perfect sense to most of us and it has even been a long-standing anecdotal claim that planted peanut acres are inversely affected by the price of cotton. That is when cotton prices are high, farmers will rotate more acres out of peanuts to capitalize.

We are, if nothing else, always up for a research challenge! However, despite our best efforts we were unable to find any study or mathematical model to substantiate this claim. And even our own economic calculations were unable to find any such correlation at the national, state, or even county level. Surprised, we looked closely into what might be happening.

Peanut producers operate within a Federal price risk support program (which we will cover in great depth in our next article). Prior to 1996, USDA would limit the number of acres able to be planted into peanuts and the price support received was less connected to farm market commodity prices. Each eligible farmer was given a base number of acres for peanuts (and other program crops as well) which served as a maximum they could grow for any of the program crops. Farmers would typically fill that base number if for no other reason than being restricted by USDA base acres for their farm to devoting those acres to other crops. Thus base acreage restrictions more or less placed both a floor and a ceiling on crop planting decisions, disconnecting farmers from the realities of supply and demand.

Along with many other things, the Freedom to Farm act in 1996 allowed farmers to choose what crops to plant based on markets and potential returns rather than being capped at certain quantities of certain crops. As we will learn in our next article, a form of price risk support for the crop remains but in a very different manner.

A by-product of these changes is that now peanut processors, in an effort to secure reliable supply, predominately utilize grower contracts. These contracts provide advantages to both parties; shellers secure rights to purchase a predictable quantity from farmers known to reliably produce a high-quality crop. Growers receive premium payments if the product received meets certain quality requirements as well as having a known buyer. Separate but linked, both parties also benefit from a virtual minimum price for the grower via the Peanut Program under Title I of the current and previous Farm Bills. The combination of quality bonuses and a more or less guaranteed purchaser at a known minimum market price reduces the risk of growing peanuts to the grower relative to other crops.

It would appear that this mixture of continued federal price support, changes with the Freedom to Farm Act, and marketing through production contracts has created an environment where farmers choose to maximize their peanut acres in lieu of another commodity under typical market conditions. They plant what they are able to get a peanut contract for, and then make strategic planting decisions for the remainder of their acreage.

Input Costs

The cost of production for any good is going to affect the farmer’s willingness and ability to produce. As input costs rise it pinches the profit margin, or even eliminates it. The University of Georgia 2024 Irrigated Peanut Enterprise Budget attributed $783.50/acre in variable costs. Looking at prices paid indexes for 2022-July 2024 we can clearly see that farmers are paying more each year for the combined categories of fuel, fertilizers, chemicals, machinery, and general inflation. Especially in the critical months of January through April when farmers are typically purchasing inputs for the upcoming growing season.

Beginning Farmer Stocks

Beginning farmer stock amounts gives us another clue into the interesting dynamic between supply, demand, and international competition of a commodity. One could look at stocks as a nationwide collective inventory that sets the base for what the supply side of the equation will look like for the upcoming marketing year.

Weather

Where our peanut acres are concentrated also exposes them to storm systems from the Atlantic ocean. Mother nature is a most unpredictable partner in peanut production. Inclement weather at the wrong time can prevent planting, decrease yield, or negatively affect the end quality of the peanuts. In 2018 it was estimated that Hurricane Micheal cost peanut growers $10 to $20 million in infrastructure, stored peanuts, and yield[2]. While we can’t stop hurricanes, or always protect crops from their force, advanced data and mapping can help us better understand the risk extreme weather can pose to peanut acres. Our map, below, dictates the path of Class 1-5 hurricanes in the past 20 years .

Aflatoxin

Wet weather is not the only thing we have to worry about. Extremely hot, dry conditions during production and late stages of peanut development can lead to unsafe levels (above 15ppb total) of pre-harvest aflatoxin levels. Aflatoxin is a mycotoxin produced by the fungus Aspergillus flavus and is toxic to both humans and livestock. There is a general feeling that high aflatoxin years are becoming more frequent[3]. The chart below from the Georgia Federal-State Inspection Service shows by year the percent of SEG 3 farmer stock and edible lots that exceeded the USDA max aflatoxin limit.

A recent example was the 2019 growing season in the Southeastern United States where extremely dry and hot conditions caused about 30% of the shelled runner peanut lot to be rejected because of unsafe aflatoxin levels and had an industry wide economic impact of losses reaching $52,28/MT[4]. With growing concern over increasing average temperatures and availability of water for irrigation, it is highly possible that we could see increased aflatoxin impacts on supply in the coming years.

Producer Expectation of Price

A final factor in the supply curve of an industry would be the producer’s expectations of what price they will receive for that good. While this is a factor that drives all commodity supply, peanut producers’ perceptions are additionally influenced by government support programs. There are a lot of misconceptions and confusion about USDA peanut programs and the governments involvement in peanut supply and pricing. To give this subject the attention that it deserves we will be dedicating our final installment of this series to bringing clarity to how and why these programs work.

(1)3.2 Supply – Principles of Economics (umn.edu)

[2] Georgia farmers face more than $2 billion in losses from Hurricane Michael - UGA Research News

[3] Butts | U.S. Peanut Quality: Industry Priorities to Mitigate Aflatoxin Risk from Farm to Consumer | Peanut Science

[4] Butts | U.S. Peanut Quality: Industry Priorities to Mitigate Aflatoxin Risk from Farm to Consumer | Peanut Science